Charretting for Results

Samantha Delabar and Meredith Payne of BHDP Architecture discuss how design strategists and business leaders must learn to effectively work together to transform workplace design.

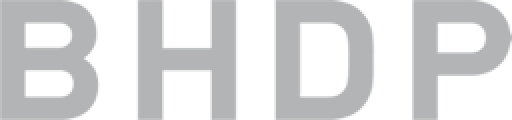

Example Results from a successful charrette

For the past half century, design often referred to an individual who asked a few questions about a problem, went away for a period of time, and returned with well-crafted ideas to present as solutions to clients’ problems. Referred to as the master-design model, many architects and interior designers today developed their technique using this process. However, with the ever-increasing advancements in technology, the problems of design are entirely too complex to expect any one person to create the “perfect” solution. Here’s where charretting—the planning and design process where participants work collaboratively to find solutions—can play an important role. Its definition involves any interaction in which a group of designers drafts a solution to a design problem. The structure of each design project comes with a different set of stakeholders on the design side. However, more progressive design firms are expanding their definition of charrette to include stakeholders on the client’s side as well. In practice this form of charretting is a “graphic conversation” between designers and those who are intended to benefit from the design.

The Foundation of Charretting

It’s common knowledge among doctors that no two heart attacks are alike. This is one reason why they need their patients to play critical roles in deciding the best treatment plan. For comparable reasons, the design process calls for the same level of teamwork. Collaborative sessions are key. The intention is to link the genius of professional designers as closely as possible to the end user’s need, aspirations and behaviors. Getting the right people in the room to define, arrange, and conceptualize a future place to inhabit higher value work is the wisest and simplest answer. Each side (design strategists and business leaders) comes to the table with a unique set of knowledge and expertise to help carry out the charrette. Usually, those representing the client side don’t draw, nor have they been trained to consider a space in terms of work settings. That’s up to the design strategist. On the other hand, what business leaders bring is their intense knowledge about the heart of the company, the office space needs, assigned and unassigned desks, future expansion plans, and other basic elements of what should comprise their office.

Another foundation of charretting is the use of storytelling scenarios to steer clients into the design process. Start by encouraging company executives to recount stories about special events, important meetings, late nights, and other dealings that have transpired throughout the years. Engage in active conversations with leaders so they can understand how a decision like, “Does everyone get an assigned seat?” impacts the outcome. In the end, conversation is translated from the business need to people behaviors, and ideally efficient space is created.

The Five-step Process for Implementing the Charrette Model

- Clarify the strategic intent. Here, the focus is on bringing to life the words most often used when describing workplace needs. Yet, many clients provide only one word descriptions like: fun, innovative, collaborative, and productive. Go one step further toward clarifying these terms by developing word pictures. For instance, “fun” might be two people sitting in a comfortable spot—having just finished a heap of work—and they’re relaxing. “Innovative” evokes an aura of discovery and shared visions—perhaps depicted by two people having an aha moment during a work session. “Collaborative” could be three or four associates discussing the merits of a new system. And, “productive” might be a meeting wrapping up or someone collating a final presentation.

- Provide visual cues. Abundance comes to mind when describing this phase. A full spectrum of space types must be provided for a client’s options. Visuals go beyond furniture types and room shapes. They require envisioning how each setting might perform when people are inserted. For example, through identifying how many work behavior types are in play and picturing how a spontaneous meeting might play out, the value of a design option can be immediately explored and graphically represented. What about meetings of between eight and 20 people? Is this a spacious conference room, or is it wiser to break it down into a neighborhood of work areas? Once these visual cues are discussed, the design elements are added in to see how they affect the space.

- Create an intimate design experience. Each senior leader (client side) should be paired to work with one design strategist. Make sure these are one-on-one sessions—and the use of tracing paper is mandatory. There, a scripted conversation is written based on the design/business strategy. Most often it is the design strategists who become responsible for the graphic representation of ideas. Often they ask clients to take a “day in the life” approach to assist their process. What activities normally make up a day’s work? The tricky part of this endeavor is that the strategist must remain focused on capturing the developing vision of the senior leader—and must allow the process to steer itself toward the best physical conclusion. True magic develops when the client becomes comfortable enough to pick up a pen and add to the work being created in front of their eyes.

- Connect the sketches to the real world. Help leaders link the pictures to their workplace through a look and feel image exercise. Using this step helps strategists avoid asking the client to employ the “red and green dots” method—where leaders use these colored stickers to indicate what they like and don’t like and what their personal preferences are. Instead, the goal is to find images that seem to come closest to representing what’s been sketched.

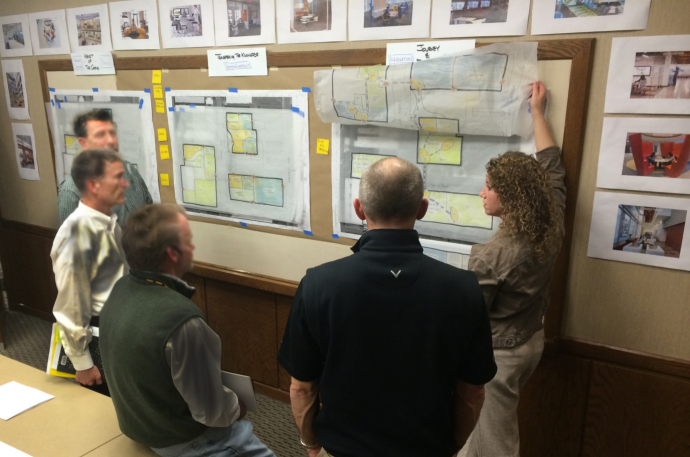

- Allow leaders to present their ideas. Each leader should be given presentation time to share ideas with other leaders. Since they have played an instrumental role in the creative process from the start, leaders are more likely to be comfortable discussing the merits of their charrette results—including what they believe is mandatory and what isn’t. Ideally, the end goal is for each leader to cross-pollinate his/her idea with others in such a way that the whole team can evolve shared ideas into a cohesive concept.

Charretting Challenges

There are two points of challenge with charrettes that, if conquered, seem to drive more successful outcomes. The first stems from whether or not a designer will leave his or her ego at home during the charretting process, and that’s not being stated with malice. Designers should have a strong sense of self-worth and that awareness should be revealed through a potent degree of pride toward their work. However, for charretting to succeed, an attitude of collaboration is essential. In other words, designers need to be willing to share their central role—as the creator—with the other stakeholders. If this can transpire, the charrette likely will undergo an energetic, agile session full of prompts that are intended to unite the designer with the end user’s need. Keep in mind that it’s hard to avoid the uncertain, esoteric graphic conversations that kick off most charrettes. But, they’re normal. It takes the awkwardness of those initial ambiguities to arrive at the right solutions.

The second challenge is trying to get business leaders to realize and accept that they can be creative in design (even if just for a short period of time). By assuring leaders they have this ability, it supplies the confidence needed to produce their ideas through the process. As a result, business leaders shed their expectations that a designer has to ask all the questions, then leave for a few weeks, and return to present the “big reveal.”

BHDP’s Samantha Delabar leading final charrette results with senior leaders

The Relevance of Charretting in Today’s Workplace

BHDP’s client data support why charretting is significant. Throughout the firm’s 80-year history, associates have interviewed clients and learned time after time that assigned work cubicles in the United States are more than half empty at any given point in a workday. These findings suggest that America has moved from the more production-oriented assembly line work to the understanding that people don’t need to be at their desks to get their work done. Although office design is shifting away from assigned to more collaborative spaces, some managers still vie for assigned seats whether they use them or not. For this reason, the change is occurring more slowly than some would like. In the end, coming to realizations about available space demonstrates the value of the charrette. By making a design experience alive and active, it becomes a more visual, results-oriented experience.

Believe in the Charrette

In the world of modern design, the industry paradigm is being shattered and designers are learning to yield the pen. Once design strategists and business leaders work comfortably on the same piece of sketch paper—that’s when workplace design will transform offices away from rigid, assigned spaces and more toward collaborative, productive areas. Since the open workplace evolved out of 20 years of increased collaboration, it now calls for replacing the master-designer model with a process like charretting—allowing stakeholders to share in a graphic conversation to create results. It makes good sense because those who have a stake in the outcome are more likely to believe in it—and believing in it means defending it and taking action on it.

Originally published in Workplace Design Magazine.

Author