The Workplace as a Social Organism

While working from home certainly has merits, the long view is that organizations prosper from the hard-won social captial of connections among people.

The workplace is a social organism. BHDP’s large common space, featured above, provides movable, flexible furniture and creates the opportunity for collaboration and idea sharing.

If the coronavirus pandemic has taught society and business anything, it’s this: the workplace is more than a composition of spaces, furniture, tools, and people. The workplace is a social organism. Gartner research illustrates the key to keeping highly motivated talent is not hard—it’s soft. People who feel socially connected to their organizations are more likely to remain, perform, and thrive. With a substantial part of the workforce stuck in WFH, that premise has never been more challenged than at present. Not surprisingly, the workplace design community is left wondering how to weave organizational culture from the threads of a fragmented and disconnected social fabric.

Pro-social behavior defined

While working from home certainly has merits, the long view is that organizations prosper from the hardwon social capital of connections among people. Relationships are the sum of shared experiences over time. Although technology provides the ability to communicate with one another ad nauseum, it is no substitute for presence. With vanguards like Google, Facebook, Nationwide, and Twitter considering extended or even permanent work-from-home strategies as a component of their total workplace programs, companies pushing for a return in force might appear cavalier.

It’s true that employees, managers and others can meet, get stuff done and deliver some results. On the other hand, it is more difficult to establish the type of soft connections that enable organizations to remain resilient in the face of strong headwinds. When physically distant, people struggle with enacting prosocial behaviors. These voluntary acts intended to “benefit others or society as a whole” are the altruistic fabric that bind strong organizations.

Prosocial behaviors have many cognates. They include pitching in, rolling up sleeves, and going the extra mile. All illustrate a person’s willingness to put another or even the organization above oneself. While these acts certainly occur in the remote world, they are more difficult to recognize, model and celebrate.

In addition, researchers have found that prosocial behaviors have a significant impact on psychological safety, the bedrock upon which strong teams are anchored. E.O Wilson, the father of sociobiology and biodiversity stated, “Organisms, when housed in unfit habitats, undergo social, psychological, and physical breakdown.” The greatest risk for all organizations at present is the atrophy of its teams.

“Organisms, when housed in unfit habitats, undergo social, psychological, and physical breakdown.”

E.O Wilson

The shadow of extended absence

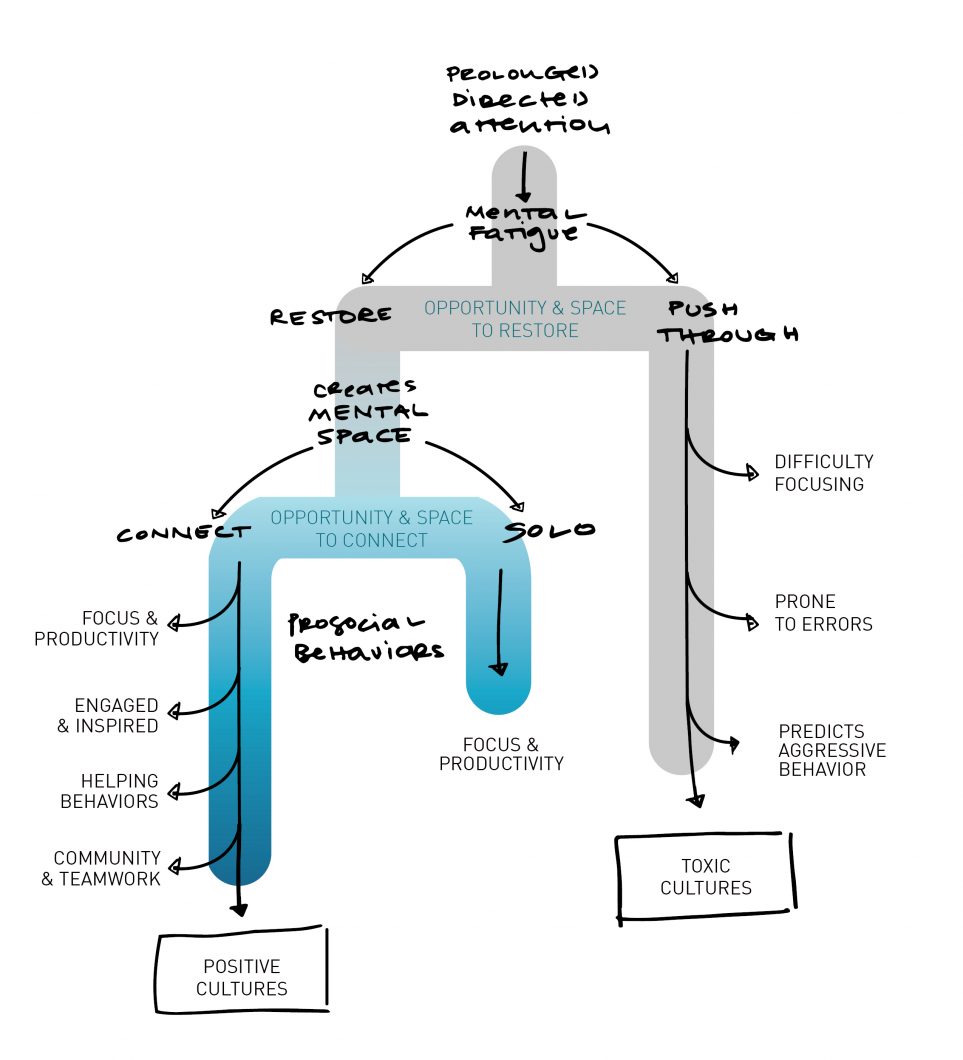

While the jury is out on whether people can be just as productive working from home, Americans are demonstrating a propensity to work longer hours. This increase in online activity comes at the expense of two fundamental human needs that do not neatly fit into Maslow’s hierarchy: the need to restore and the need to connect. Consider the endless stream of videoconferences that individuals and teams have endured over the last two months. When not afforded the opportunity to recover from mental fatigue, psychological research indicates that humans experience distress, have difficulty focusing, are prone to errors, and become increasingly aggressive. These are the precursors to toxic, antisocial behavior, and they stem from a lack of mental restoration.

Similarly, personality differences aside, people have a fundamental need to connect with each other. While virtual happy hours might be a substitute for team bonding and rapport, they cannot sustain organizational culture indefinitely because people work better together.

While virtual happy hours might be a substitute for team bonding and rapport, they cannot sustain organizational culture indefinitely because people work better together.

Research from Stanford shows performance and persistence on challenging tasks improves when people believe they are working with others. The researchers also found that a sense of collaboration and teamwork makes work more fascinating, and even fun, leading to persistence over the span of weeks (Butler, L. P., & Walton, G. M. 2013). People aren’t meant to work alone. Lonely workers aren’t just psychologically distanced from others, they’re distanced from the meaning, support and inspiration that communities provide. Therefore, they are less engaged, productive and satisfied with their jobs. (Carr, P. B., & Walton, G. M. 2014)

The psychology community has long been fascinated by the importance of altruistic behaviors in fostering positive communities. The research finds pro-social behavior to be the “the strongest and most reliable predictor of operational success, including organizational performance.” (Mallén, Chiva, Alegre, & Guinot, 2014) Prosocial behaviors connect individuals to each other and to shared meaning, providing self-esteem and motivation. These compassionate acts are the lifeblood of communities (Greene, J., & Haidt, J. 2002) leading to greater organizational commitment (Dutton JE, Lilius JM, Kanov JM 2007) and an engaged workforce.

This graphic shows the harmful effects on individuals when they are not given the opportunity to recover from mental fatigue.

Ultimately, prosocial behaviors don’t just determine if people are happy, they “positively impact the entity’s bottom line, and improve its long-term outlook.” (Vieweg, J. 2018) While the physical welfare of the workforce is obviously of the utmost concern for all organizations, the fact remains. The longer businesses and society linger in the present state, the darker the shadow cost of extended absence will be.

Design for social connection

Regardless of what the future of work holds, a simple biological fact remains: people need people. Strong organizations are bound by informal social contracts that are inked in small, prosocial increments. The built environment has traditionally facilitated these interactions and will continue to play an infrastructural role in the future. Technology, as it always has, will facilitate society’s ability to connect with each other. Digital space, however, is not yet a substitute for physical connection. Look no further than the pre-COVID statistics on loneliness to understand the psychological and emotional cost of physical and social isolation.

Prior to the pandemic, the sad fact is that workplace design was becoming more a math exercise than a creative pursuit. Playing the numbers to accommodate a growing population in a fixed amount of space isn’t design. It’s an equation. The knee-jerk reaction to the current crisis was, unfortunately, a continuation of this lopsided logic.

People aren’t meant to work alone. Lonely workers aren’t just psychologically distanced from others, they’re distanced from the meaning, support and inspiration that communities provide.

Across the spectrum of scenarios currently being considered, the most promising is the concept of workplace as social center. In this model, the workplace becomes a central hub as in a student union, civic center, or social club. The space is not apportioned into individual units but rather the collective embodiment of the organization or institution. Corporate real estate then assumes responsibility for building and sustaining the organization rather than managing seat counts and furniture plans. As organizations pursue the hard work of evaluating the value of their assets, leaders will need to invest in environments that foster social and emotional connections. The alternative approach—continuing to pursue the notion that people amount to seats and divesting accordingly—is counterproductive and pulls at the social fabric of the organization.

This article was originally published in Workplaces Magazine. If you’re interested in more thought leadership surrounding COVID-19’s effect on the work environment, check out Drew’s recent article, Five Futures for the Post-COVID-19 Workplace.