Creating Communities of Work: Creating Place in the Workplace

Introduction

Over the past two years, we have all witnessed the rapidly shifting nature of work, and the impact it has had on the places where work happens. The untethered office — which got its start with advances in digital technology, online connectivity and mobility at the turn of the millennium — has accelerated into a full-blown ‘remote work’ phenomenon during the COVID-19 pandemic. While this new way of working has provided employees with a sense of freedom, there have been problems when untethered and remote tip over into unmoored and isolated.

In recent studies, 99 percent of respondents say they value the flexibility and security of working remotely.1 In addition, 42 percent have grown actively uneasy about returning to in-person work and are sceptical of the need for traditional workplaces.2 The challenge for employers is managing the tension between employee preferences for remote work and the need to foster collaboration, connectedness and a sense of corporate identity provided by the workplace.

Community design,3 which has its roots in urban4 planning and focuses on enabling social connections and a sense of shared purpose by putting people at the center of the design process, has much to teach corporate real estate (CRE) professionals about this conundrum. An underlying concept of community design is that ‘place’ can propel the relationships that lead to commitment and a shared mission for a group or organization.

So, how do you inject energy and vitality into a workplace so that it draws people in and encourages them to stay? How do you improve the sense of community, cohesion and connectedness when people are working both in and out of the workplace? How do you build in versatility and make it easier to work collaboratively? How do you increase the likelihood, in a time of choice, that the workplace is indeed a place people regularly choose? These are all questions that Fifth Third Bank, a diversified financial service company and one of the largest banks and money managers in the USA, faced as it reimagined its downtown headquarters for an untethered and, with the onset of COVID-19, pandemic-inflected future.

Fifth Third Bank: The Challenge of Transforming a Campus and a Culture

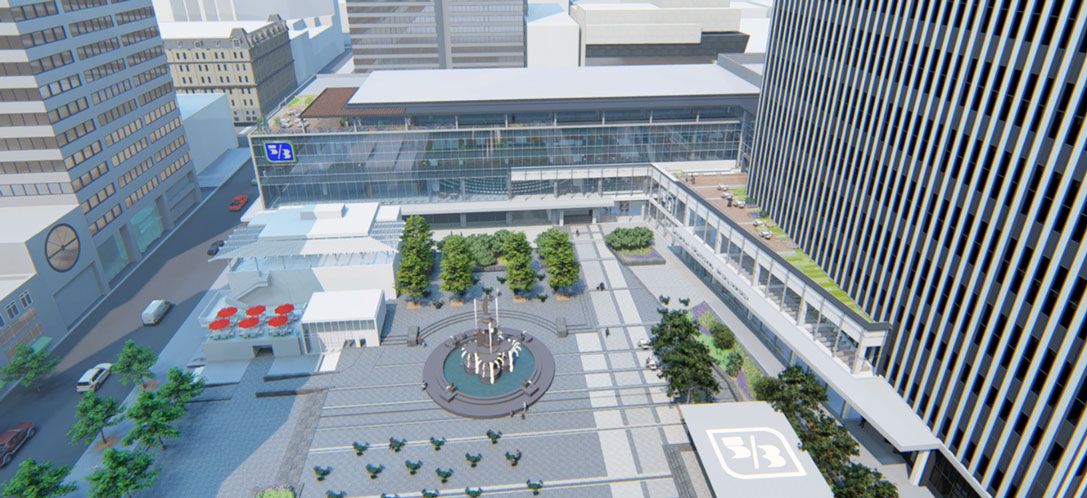

In 2017, nearly two years before most of the world had even heard of coronavirus, Fifth Third decided to transform its downtown headquarters on Cincinnati’s Fountain Square. The 50-year-old campus, located in the heart of the city and sitting at its central gathering place (see Figure 1 below), was due for a comprehensive overhaul. The mid-20th-century urban campus suffered from an unintuitive and unclear layout for both employees and visitors — two separate buildings without a clear ‘front door’. It had limited meeting and collaboration spaces with restricted technology and no flexibility. And its traditional office floorplates tended toward private offices and cubicle farms dedicated to heads-down work and not adaptable to the present, nor certainly the future, of work. There was no cohesive campus experience; the physical headquarters, contrary to established Fifth Third’s culture, was not sufficiently connected to its location and the community; and employees had challenges connecting with each other as the nature of work was changing.

Beyond these practical challenges was a more foundational one: how to transform the campus space to enable employees to be their best selves, within the organization and the community. The bank’s workplace team defined the project’s objective both simply and expansively: When you walk out the door, you are better than when you came in … and you want to come back.

Two years into the transformation, the onset of COVID-19 in early 2019 both compounded the logistical challenges and threw into stark relief the larger premise that ‘place’ is truly important to everyday life and work and can foster physical and psychological safety, connectedness and socialization. The question became: could the headquarters function as a compelling invitation to remote workers to come back together and connect as part of a vibrant community of work?

Figure 1: Early concept rendering of Fifth Third’s HQ campus on Cincinnati’s Fountain Square

Communities of Work through Community Design: A Primer

Before addressing how Fifth Third translated community design principles into physical designs for its workplace, it may be helpful to understand from where these ideas derive.

To do so, one must first ask what makes a great community? For some, it is a wealth of amenities and activities including opportunities to learn, be entertained, or rest and recharge. For others, it is a welcoming spirit and chance to connect with others. The physical space itself — with clear pathways and central gathering places — plays a big part in whether a community works. But there is also the intangible sense of ‘place’ which a successful community exudes, its ability to celebrate and reflect the culture of those living within it (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: The vitality of Fountain Square on display serving as a place for the Cincinnati community with Fifth Third as a backdrop

The central insight of community design for the workplace is that workplaces, like most communities, play a unique — even central — role in our lives. Our identities are tied to the workplace and our co-workers, much like they are to our cities, towns, neighborhoods and communities.5 Work and urban spaces succeed when they can connect people, ideas and resources to heighten interaction and provide an engaging experience. To help create those connections between people, their community of work and the greater community, it is appropriate to apply the principle to ‘design a thing by considering it in its next larger context — a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, an environment in a city plan’.6

These similarities between communities in physical neighborhoods and workplaces suggest that urban design and planning7 has much to teach us about creating places and experiences where people want to work. The following five urban design and planning principles have special relevance for workplaces today.

Rethinking me and we spaces

Urban planners and designers, grappling with congestion and overcrowding, especially in dense city centers, have had to rethink the emphasis placed on private versus public spaces. Their solution has often been to bring people out of their cramped apartments and other living spaces into open, shared amenity areas such as courtyards, parks or open-air markets.

Designers can apply the same thinking to workplace design, where modern workplace ‘cube farms’ can be seen as the equivalent of ‘sprawl’ in urban design. While there will always be a need for private workspaces (me spaces) when people require privacy or quiet to focus, building community and connections at work requires providing for a diverse set of options to collaborate and ‘catch the culture’. This translates into an increased need for conference rooms, flexible spaces for ideation and informal knowledge exchange and seating arrangements or amenity areas that encourage social interaction (we spaces) (see Figure 3). This is especially true post-pandemic as more and more heads-down work is done at home.

Figure 3: Adjacent ‘we’ spaces within the Fifth Third workplace to encourage social interaction and collaboration View Project

Mixed-use gets more use

Urban design and planning professionals have long recognized the benefits of mixed-use districts that bring residential, commercial, retail and institutional assets together. People want to work close to where they live and be able to easily access resources such as shops, childcare, schools and other services. The closer these resources are to home, work and each other, the less time is spent traveling among them, leaving more time for more meaningful activities.

Similarly, companies need to consider the diverse needs and expectations of their people to increase engagement and create places where people want to work. Amenities such as cafes, fitness areas or well-being rooms are opportunities to take an office above and beyond typical ‘at work’ behaviors of the past and foster social interaction and camaraderie in the workplace (see Figure 4). This does not mean to replace those opportunities provided externally, but it is important to provide some internal opportunities for stepping away from formal work and recharging.8

Figure 4: Mixed-use space in the Fifth Third workplace allows for a diversity of activities to happen simultaneously

The significance of stickiness

Getting people to visit or return to an area is all about making it an experience. Urban designers and planners have used the term ‘stickiness’ to describe spaces that attract people and make them want to stay. Historic main streets and curated alleys9 exhibit stickiness. Our main streets are places where people want to go, stop, see and be seen and ‘get stuck’. Things that enhance stickiness in urban environments include good outdoor seating, music, art, food and shopping that reflects the local area.

Stickiness can be applied to workplace design by creating destination points and ‘centers of gravity’ which encourage people to come together and connect in both planned and unplanned interactions. These can be reception areas, workplace cafes or town green-like central gathering places which are open, inviting and often provide amenities. These areas typically offer a variety of seating options, are somewhat customizable, feature natural materials and use warm lighting to create an intuitive, thoughtful and authentic experience and the opportunity to ‘collide and connect’.

The crucial role of legibility

Figure 5: The Spanish Steps in Rome serving as an example of Lynch’s node (plaza), path (steps) and landmark (church)

The urban design and planning community has also long known that how people understand an environment can have a major impact on how they connect to it and whether they feel part of a shared enterprise. In 1960, Kevin Lynch published his ground-breaking book, Image of the City,10 the result of a five-year study of Los Angeles, Boston and Jersey City, in which he argued that people form mental maps of their surroundings based on archetypal elements such as paths, landmarks and edges. These provide familiar reference points and ways for people to relate to an urban environment (see Figure 5). To quote Lynch, ‘Above all, if the environment is visibly organized and sharply identified, the citizen can inform it with their own meanings and connections. Then, it will become a true place, remarkable and unmistakable’.

Lynch’s thinking can be applied to workplace design, creating human-scaled spaces with intuitive nodes, pathways and districts. For example, coffee and food hubs become nodes along main office thoroughfares where interactive display walls and flexible seating create ‘edges’ that encourage employees to linger. All of these are integrated into work areas functioning as neighborhoods that can be layered with additional destination points such as meeting spaces or other office landmarks.

The essential truth: Place is people — people is place

While physical design elements play an important role in providing an organizational framework for thriving communities and workplaces, clear wayfinding or thoughtful decorative elements are not enough. Psychologist David Canter developed a theory of ‘place’11 comprised of three elements: social (activities), physical (attributes) and cultural (meaning). Focusing on just the first two of these will not fully support the creation of a place where people want to be and connect with, which in turn can result in a missed opportunity to positively affect both attitude and productivity.

The overarching goal of community design is to include those people who will be affected by decisions in the actual decision-making process. It is easy to see how this is key to creating a sense of ‘place’ that celebrates and reflects the culture of those living or working in a particular location, supporting and reinforcing their values. Urban designers and planners have long understood the critical importance of social and cultural meanings in revitalizing cities by promoting connection and belonging.

True communities of work do the same. They focus not just on the physical attributes of the workspace but also on how employees connect to work — from the various activities they undertake throughout the day to the culture they are part of and their evolving needs and aspirations — and to each other. This requires a collaborative effort between the users of the workplace and those who help craft it. It is an integrative process in which architects and designers co-create a physical environment alongside and with the input of people within the client organization. Only by understanding a company’s activities and its norms, values, aspirations and purpose — its culture — is it possible to create a place in the workplace that will truly support employees so they can do their best work possible.

Defining Communities of Work At Fifth Third

As the Fifth Third workplace team and its architect partner, BHDP, collaborated on a design for the new headquarters, their overall goal was to create an environment that functioned like a community while appealing to increasingly mobile and disengaged workers. To this end, the renovation had seven key success metrics.

Balance a remote workforce

The assumption was that employees would continue to work from home at least part of the time post-pandemic. The physical spaces in the buildings have been redesigned to acknowledge this fact by providing the work support, resources and experiences that remote work could not replicate.

Reimagine work while enabling a return to place

The renovated headquarters is not only drawing people in, it also is providing an opportunity for interaction to support employees in their work. By prioritizing scale and diversity of space over headcount in newly renovated areas, this new space is breaking down barriers to humanize the workplace with a welcoming, neighborhood feel.

Foster collaboration, innovation and corporate identity

An emphasis on versatile meeting and collaboration spaces was a given to address Fifth Third’s challenge of limited conference and meeting rooms. The key was designing a dynamic, exciting space that employees would identify with and be drawn to, filling the environment with the energy that facilitates interaction and ideation with a wide variety of large and small group gathering spaces in both formal and informal settings.

Be flexible in design, which can have a powerful effect on people

People like the choice provided by a variety of spaces, including private workspaces for quiet, heads-down work and opportunities for face-to-face interaction and exchange of ideas. They also like the flexibility technology can offer. The new space responds to all of these needs in a versatile way.

Be a living example of the idea, ‘the on-site is the new off-site’

Off-site meetings have traditionally been dedicated to big picture strategy, goals or projects, conducted away from the office to encourage ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking and more relaxed interchange. A key goal of the headquarters renovation was to foster a similar spontaneity, an opportunity for both planned and unplanned exchanges, where people can form new relationships and generate new ideas. Furthermore, the headquarters could have the power to provide all of the benefits those off-site sessions formerly offered.

Create vibrant cultural connectedness

The renovation should embody the identity of the people who would use the space through the careful integration of featured design elements inspired by corporate and community values. This included both Fifth Third employees — encompassing those who work in regional offices as well — and the larger Cincinnati community.

Connect the Fifth Third community of work to the community it serves

Last but far from least, the campus renovation had to welcome in clients and the community as an integral part of the Fifth Third family, whether for collaboration or for insight into the bank’s connection to the community. By minimizing physical barriers and maximising visibility into the building, emphasis was placed on creating a welcoming space to support both programmed and spontaneous moments of community engagement.

The Results: Project Connect, The Forum and The Towers

The Fifth Third headquarters renovation has been a multi-year, multi-phase project addressing everything from the ‘front door’ of the campus, to meeting and collaboration spaces, to legacy floorplates in the campus towers.

Establishing cultural connections

The most outwardly visible portion of the comprehensive overhaul is called ‘Project Connect’. Previously, the campus suffered from two separate buildings with no clear entrance and confusing or absent wayfinding. Both employees and visitors had a hard time navigating their way around the campus. The confusion also presented security issues.

To improve legibility and transparency, the two buildings on the campus, the Fifth Third Center’s tower and the William Rowe Building, were physically connected via an atrium. Beyond joining the buildings, the new atrium entrance serves as a central space where employees can connect during a time of shifting work habits and absorb the culture of the company (see Figure 6). It also serves to connect the bank to the larger Cincinnati community.

Figure 6: The interior of Project Connect provides a space for employees and visitors alike to interact and find respite

The design of the atrium is a simple glass volume tailored to complement but stand apart from the minimalist, mid-century architecture of the existing buildings. The primary architectural feature is the glass curtain wall which captures natural light and maximizes sightlines into and out of the new lobby space, transparently connecting the bank to the public space on which it sits. To reinforce this relationship, a diagonal line creating the wedge-shaped atrium is oriented to the Tyler Davidson Fountain, the true focal point of Fountain Square, where the campus resides.

Glimpses of the fountain reflected in the glass as visitors approach the new ‘front door’ provide moments of visual depth and symbolism (see Figure 7). By mirroring the contextual and communal elements of the underlying urban design, the new entrance and lobby space function as an indoor extension of Fountain Square, giving visitors and community members open access during business hours and special events.

Figure 7: The new ‘front door’ within the diagonal glass curtain wall of Project Connect (bottom) improves lack of visual clarity from the original campus design (top)

Inside the atrium, there are also design elements which locate the bank within its civic ecosystem. An acrylic sculpture designed by sculpture artist Danielle Roney hanging above the lobby uses a data algorithm to project the words Fifth Third’s community of fans and followers is using online. The experiential graphic design (EGD) inside the space highlights Fifth Third’s brand and vast community involvement throughout the years. One wall, covered with dark wood panels and lush greenery, highlights specific community outreach programs like ‘Operation Hope’. In the stairwell to the second floor, design elements such as repurposed pavers from Fountain Square and a digital water wall with sound immersion and scent activation that simulates the activity and smell of fresh water from the fountain also anchor the bank to its physical surroundings.

In addition to unifying the campus and connecting the community of Fifth Third to the community outside, the spacious atrium area offers both employees and visitors multiple activity options: working solo, meeting, visiting the NextGen branch — a customer-focused banking center — or exploring the Fifth Third Museum, creating a ‘sticky’ place (see Figure 8). On the second floor, a modern, flexible, technologically enabled meeting and collaboration space called the Forum was specifically designed to provide the opportunity for collaboration, ideation and connection, which is at the center of communities of work.

Figure 8: Project Connect exhibits multiple moments of ‘stickiness’, such as this tucked-away space for gazing out onto Fountain Square Plaza (node/landmark) and people watching or connecting with people along the interior ramp (path)

A place for bringing people together

In the entryway to the Forum, a large-scale, three dimensional ‘sign’ (which doubles as a seat) greets visitors, welcoming them to this unique, new space. An undulating wood ceiling, reminiscent of the movement and flow of the Ohio River, combined with wood accents in the hallways act as powerful wayfinding and encourage people to move deeper through the space (see Figure 9).

The Forum features a variety of flexible conference and meeting rooms to invite interaction, balance collaboration with concentration and reinforce company culture (see Figure 10). A large, multifunctional space at the centre of the Forum can be configured to support meetings of up to 200 people. Further inside, an original bank vault has been reimagined into a warm, inviting, more informal space with private booths along the wall and a cozy meeting room with sofa and TV. Enhanced by dynamic textures and unique details, including a metallic ceiling, blue carpet and funky furniture, the vault serves as a destination point within the new headquarters, inviting employees back to the office with its combination of functionality and singularity. Some of the safe-deposit boxes from the original vault even remain on the wall, while others were removed and repurposed to create space for photos and storytelling opportunities.

Although the Forum and Project Connect are the most visible manifestations of the Fifth Third headquarters renovation and its community design principles, a multi-year initiative begun in 2017 has also transformed the employee spaces within the downtown tower.

Figure 9: The entryway to the Forum, a new meeting and collaboration space at the centre of Fifth Third’s community of work

Building neighborhoods

The tall tower — a 31-floor, classic, mid-20th-century skyscraper — was, until recently, a throwback to the mid-1980s and earlier models of work. Employees got off elevators to face a small, confined lobby space and a wall of partitions leading to offices on the perimeter of the building. The emphasis was on privacy and providing office views. Open-plan workstations and cubicles in the center of the floorplate were primarily designed to maximize efficiency and productivity. There was little emphasis on human interaction and engagement or space devoted to common spaces and amenities. ‘When I first started working at Fifth Third, the physical workspace reminded me of an old 80s movie. It is great to work in a more modern environment.’12

To create a more welcoming and socially inclusive environment for team members in the tower, Fifth Third and BHDP completely transformed three-quarters of the floors, building around the concepts of ‘commons’ and ‘neighborhoods’. The commons are generous lobby and gathering places that include a combination of a break room, kitchenette, various seating options and amenities (see Figure 11). Situated in the center of the floor, they are designed to function as landing zones for groups of employees to intersect and connect in ways they otherwise might not as part of their regular work routines.

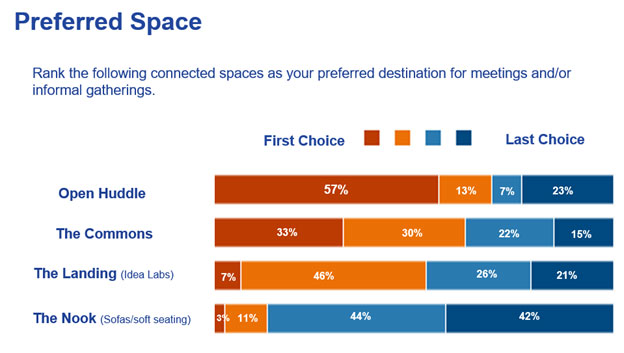

The long corridors of walled-off offices and cubicles — the veritable anthesis of community — have also been converted into neighborhoods of open-plan workspaces for 18–20 people. This small scale and massing supports people while breaking down barriers and humanizing work. Neighborhoods are divided by visual screens and a mix of open and enclosed activity areas such as phone, conference areas and huddle rooms (see Figure 12). Standard design elements such as ‘community walls’, which allow employees to post ‘call and response’ messages and hang personal items, encourage interaction. ‘The workspace is more modern, brighter and cleaner. Although there is less privacy, it makes for easier collaboration and interactions.’13

Figure 10: Flexible spaces can be opened or closed off from circulation areas within the Forum, creating numerous types of formal and informal spaces for social interaction and collaboration

The few traditional offices which remain on each floor are strategically placed interior to the floor plate and easily convertible to more public uses. An overall shift in space type ratios netted an increased allocation of conference, huddle and open collaboration settings by 15 percent — or an additional 2,000sq.ft per floor. As traditional single-function workstations were eliminated in favor of more flexible, multi-function spaces, the average total headcount on similar floors before and after renovation was reduced from 100 to 80 employees.

A significant experiential graphics (EG) program, common finishes and thoughtful wayfinding help to tie the floors together and provide opportunities to catch the culture. The EG package includes guidelines for graphic treatment in various workspaces — conference rooms, open offices, retreat zones — that are uniform but flexible. An 80/20 strategy for design elements provides that most walls, floors, solid surfaces, upholstery, lighting and other elements are consistent while allowing customization based on the unique needs and identity of employee groups and floors. The combination of wall graphics and finishes orient employees and visitors as they navigate through the space.

Like with Project Connect and the Forum, a significant emphasis has been placed on community connection in the tower. Employees are encouraged to name conference rooms after local landmarks. Graphic elements focus on local activities and historic events. Corporate stories, such as key company anniversaries and achievements, past presidents and vision and mission statements, are woven into the experiential graphic design. Beyond just creating beauty and interest, this is meant to build brand loyalty among employees, tell a story about the organization, get everyone on the same page and get them excited about coming to work. And because these elements vary from floor to floor, employees are encouraged to explore, find new things, go down to the lobby and meeting rooms in the Forum and engage in ways not possible in the past.

Figure 11: An example of a ‘commons’ for providing additional ‘we’ space within Fifth Third neighbourhoods View Project

Figure 12: Fifth Third conducted a post-occupancy survey which illustrates employee preference for various space types

Where to Start

While it may not be a quick process to develop communities of work, the first step is easy and essential: engage your people and listen to their input on what they need when they do come into the workplace — whether that is every day, one or a few days per week, month or year. And since most work these days is truly hybrid because colleagues, partners and clients may not always be working in the same space, it is important to think about how those working remote are considered even in the design of the central workplace. A communities of work approach and the creation of place in the workplace must acknowledge the need for equity of experience for an organization’s people whenever and wherever they work.

Like the urban design and planning principles of community design described earlier, successful communities of work will build upon a flexible and diverse ecosystem of spaces (eg individual, collaborative, social and well-being) that support a diversity of people’s workstyles with a high ratio of ‘we’ to ‘me’ spaces (eg concentrative, interactive or a mix of both) that people need throughout their time in the workplace. Critical to this is ensuring the workplace and its attributes (physical) will help attract and keep people engaged with the work and each other (sticky) allowing the easy use of the space and furniture (legibility) as well as knowing the behaviors, norms and expectations of using such.

For those looking for a quick fix to the realities of a post-pandemic workplace, it is important to realize that authentic communities of work, just like those communities found outside of work, take time to form through trust built on shared activities (social) and meanings (cultural). Creating a successful ‘place’ of work to support communities of work will necessitate a focus on people’s individual behaviors, team norms and shared expectations in parallel with the development of the physical design of the workplace.

Conclusion

It cannot be emphasized enough: putting up a brand sign, offering a bunch of amenities or fashioning other trappings of a culture is not the same as developing an authentic culture. The key to creating communities of work that enable social connections and build a sense of shared organizational purpose is putting people, their behaviors and their social structures at the center of the design process. Far from the binary balancing of form and function characteristic of more traditional modes of design practice, community design begins with the culture and identity of the people who use the space.

This starts with a shared vision, derived from open communication, with everyone involved feeling a sense of ownership. Senior management buy-in and commitment to the overall objectives of community design are crucial. The design process then begins with engagement, bringing employees from every level of an organization together to solicit input about their behaviors throughout the day, what they hope to accomplish, connections between the overall mission and day-to-day practice in the workplace, etc. This should include users and the support staff (facility managers, building maintenance, and security personnel) who will be affected by the workplace design, consulting with architects, interior designers, experiential graphic design experts and customer experience specialists. The focus is on how place can enable the relationships and social connections which lead to commitment and a shared mission for a group or organization.

A key success metric in community design is the reflection of the attributes of that community’s culture, which leads to a greater sense of attachment and pride of place for users — all things which can be measured in surveys, feedback and cultural assessment. Just like any neighborhood, safety, functionality and productivity are all very important, but attachment to place, which supports a shared identity and shared purpose, is the ultimate goal of community design.

Communities of work truly happen when places are designed based on the perceptions and expectations of the workforce — or, better yet, referred to simply as people — as well as the purposes of an organization. This leads to not only greater satisfaction with the functional aspects of the space but also a greater sense of belonging and connectedness. Taking cues from successful communities, great workplaces can be great people places. Like great cities and neighborhoods, they can express a shared sense of history, identify and purpose and through that experience, set the stage for future success.

Convergence Teams, Integrated Design and Creating Communities of Work

The success of the Fifth Third project was made possible by a strong partnership between BHDP and the bank, built around convergence teams working through an integrated design process and applying community design principles.

The benefits that an integrated design process can bring to building projects have been accepted for decades. Assembling a team with diverse expertise to collaboratively work on a project is intuitively understood to be a better approach than designing in a linear, sequential and isolated manner. Tapping people from multiple disciplines such as architects, designers, owners and others with a range of perspectives and bringing them together breaks down silos and provides opportunities for communication, collaboration and decision making. When architects, designers, engineers and others work separately on each element of a building, individual goals tend to trump overall project objectives.

Of course, understanding the benefits of integrated design and communities of work is not the same as realising them. Implementation is critical. Based on their experience, BHDP and Fifth Third have uncovered ten keys to doing this successfully, all revolving around what we call ‘convergence teams’. Points 1–5 focus on how to form these teams successfully. Points 6–10 highlight how the teams must work differently in order to truly succeed.

- Diversity of people: Having people from multiple disciplines is essential: The first step in delivering design in a truly integrated fashion is ensuring that the right people in the right roles are in the room. A convergence team of representatives from both the architect/designer and client are critical, consulting with users and the support staff who will be affected by the workplace design;

- Diversity of thought: Having people with cross-disciplinary experience is even better: As important as including people from a broad range of disciplines on the convergence team is encouraging a diversity of thinking and experience;

- Trust and camaraderie are essential: Trust and camaraderie are the fuel of a high-functioning integrated design team. Without this affinity, success will be elusive. That does not mean, by the way, that passionate people with strong personalities are an issue. Or that creative conflict is a problem. It is just critical that team members be able to leave their egos at the door and engage in an open-minded, iterative process, learning from each other as they go;

- The right attitude is as important as having the right participants: In addition to trust, successful convergence teams always strive for an attitude (or angle of approach) that there is not anything we — collectively — cannot do. Excellence comes from the sum of talents at the table, not from any individual;

- Senior management (at both the client and design company) should be aligned: The trust and attitude that drives successful convergence teams starts at the top. Principals at the client and design firm should clearly understand the project objectives and share a similar approach to community design. A commitment to co-creation is critical, as is philosophical and practical alignment on overall goals and design approach;

- Search and seek: search out the right people to engage — then seek to understand them: Once the convergence team is chosen, it should seek out the right people to develop a clear and deep understanding of project parameters, including workplace users: who they are, what they do, their goals and vision for the project. Clear, upfront agreement on these things helps the convergence team benchmark its efforts against a shared strategy;

- Meet more often and make it informal: Making fully informed decisions requires giving and getting feedback on a regular basis. Make these meetings more informal, minimise presentations and think of team meetings as working sessions. This approach enables more effective integration of new team members, as teams grow and evolve, so they quickly become a part of the tapestry;

- Create the time and space to learn: Having the leeway to learn by doing can advance both the pace and performance of a convergence team. Micromanagement, on the other hand, is anathema to integrated design. A ‘no fear’ environment is essential. If team members are afraid of making mistakes, they will not take the risks necessary to find the optimum solutions. You empower a convergence team to succeed by trusting that they will;

- Strive for client intimacy: A major benefit of investing the time and resources in convergence teams is their ability, through extended collaboration, to establish client intimacy. Design projects become not discrete tasks but part of a holistic effort that emphasises and extends the client’s culture across a range of workspaces;

- Encourage client leadership: In addition to learning, the willingness of the client lead to encourage, collaborate with and quarterback the team cannot be overvalued. When the client is fully invested in the convergence team and their role as the corporate storyteller, other members feel ‘led from beside’ (tugged and nudged forward rather than pushed and pulled). This leads to continuous searching for better solutions.

References and Notes

(1) Buffer (2021), ‘State of Remote Work 2021’, available at https://buffer.com/state-of-remote-work/2021 (accessed 1st June, 2022).

(2) The Conference Board, ‘Remote Work Survey’, available at https://www.conference-board.org/press/return-to-work-survey (accessed 1st June, 2022).

(3) For more information on the practice of community design see Association for Community Design, available at communitydesign.org (accessed 1st June, 2022).

(4) The use of the term ‘urban’, in context to urban planning and urban design, does not just apply to big cities. It is relevant to any place where buildings, spaces and people come together, including small towns and neighbourhoods as well as large districts and regions.

(5) While the terms ‘neighbourhood’ and ‘community’ are typically used interchangeably, it is important to recognise the critical difference between them: neighbourhoods are a physical container or setting for the sociocultural aspects of communities.

(6) Saarinen, E., 1873–1950, Architect, personal quote.

(7) While urban planning tends to focus on how a diversity of elements come together and work together, urban design tends to focus on people’s experience among those elements. Architecture, landscape architecture and other allied design fields play into this as well, but it is urban design that tends to orchestrate the overall experience.

(8) Allyn, B. (January 2022), ‘Architect behind Googleplex now says it’s “dangerous” to work at such a posh office’, NPR, available at https://www.npr.org/2022/01/22/1073975824/architect-behind-googleplex-now-says-its-dangerous-to-work-at-such-a-posh-office?t=1657619896346 (accessed 1st June, 2022).

(9) Urban designers and everyday citizens have found great success in giving new life to the underused spaces of alleys. One example includes the Sipyard located in an alley in downtown Urbana, IL, featuring a beer garden operating out of a shipping container and a stage for live performances all within an outdoor graffiti gallery.

(10) Lynch, K. (1964), The Image of the City, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

(11) Canter, D. (1977) The Psychology of Place, Architectural Press, New York.

(12) A direct quote taken from Fifth Third Bank’s Post-Occupancy Survey conducted in August 2021.

(13) Ibid.

This piece was originally published in Corporate Real Estate Journal, published by Henry Stewart Publications.

Want to learn more?

Listen to our podcasts about "Communities of Work" and the project referenced in this article, Project Connect with Fifth Third Bank.

Author

Content Type

Published Articles

Date

October 26, 2022

Topic

Workplace Strategy

Hybrid Work

Distributed Work